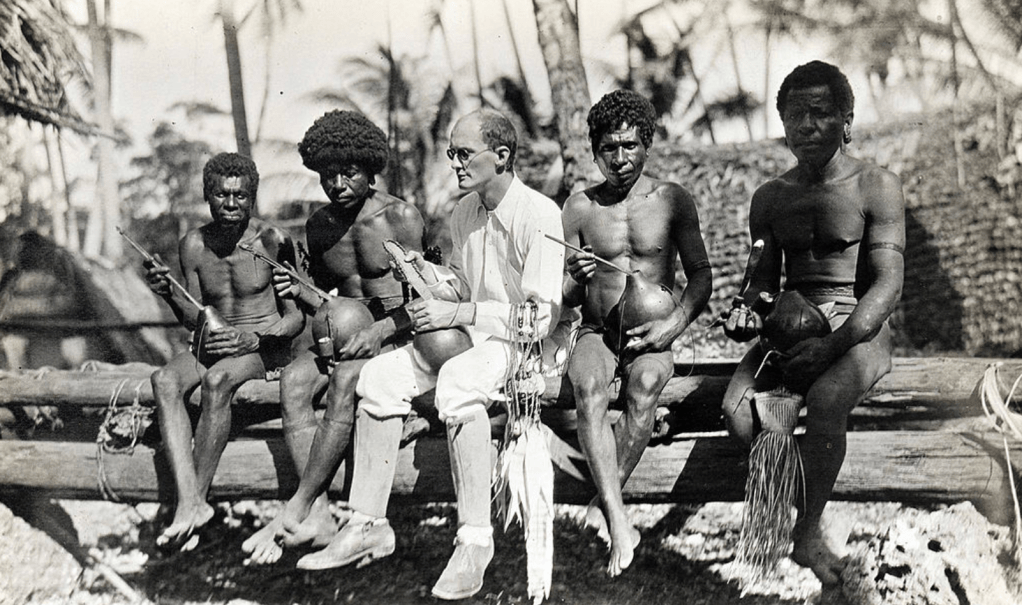

My thesis lays out the genesis of ethnographies. I achieve this by deconstructing the work of Bronisław Malinowski, founding Father of the discipline. I read him in the original language (Polish; polski), intimately tracing the passage from his diaries to his cultural monograph.

Anthropological theory is a reflexive simulacrum of epistemological preoccupations, such as mind-body dualism, which emerge also in the form of a discussion about objectivity and subjectivity in discourse. Responding to primary passions, the work of Malinowski offers a refuge for the desaltered.

Through its éloge of alterity and by straddling interdisciplinary, anthropology is the site of rearticulation of a subordination (the price to existence; Butler 1997, 48) to a sociality based on insubordination to master narratives.

The discovery of the diary after Malinowski’s death is a subversive demonstration of a controlled rupture of attachment to state authority.

It indicates the process of forming the subject through rendering the state invisible “as an ideality of conscience” (Butler 1997, 191).

© Université de Montréal

Reference: Judith Butler,The psychic life of Power, Theories in Subjection. Stanford 1997

My doctoral defense

The transcript of the defense of my doctoral dissertation presented on April 9, 2021 at the University of Montreal is reproduced below. My PhD adviser was Prof. Amaryll Chanady from the University of Montreal and the External Evaluator was the all-time Malinowski specialist (who is the editor of his full-fledged diaries) Prof. Grażyna Kubica from the Jagiellonian University in Cracow.

Le compte rendu de ma soutenance de thèse de doctorat, présentée le 9 avril 2021 à l’Université de Montréal, est reproduit ci-dessous. Ma directrice de thèse était la professeure Amaryll Chanady de l’Université de Montréal et l’évaluatrice externe était la professeure Grażyna Kubica de l’Université Jagellonne de Cracovie, spécialiste reconnue de Malinowski (et éditrice de ses journaux complets).

ON MALINOWSKI

Maja Nazaruk

My thesis sets the tone of Bronisław Malinowski’s biography against the backdrop of multicultural Cracow at the time when Poland was still partitioned. I speak of writers and artists like Stanisław Witkiewicz and his son Stanisław Witkacy, avant-garde painters, philosophers and mathematicians like Leon Chwistek, poets like Tadeusz Miciński, then medical students like Tadeusz Boy-Żelensky, composers like Mikolajus Čiurlionis, linguists and spokespersons for the movement of self-determination like Juozapas Albinas Herbačiauskas who are involved in the communal laughter at the Michalik Den Lviv pâtisserie where many delect in having their own puppet at its cabaret.

My discussion of the way in which Lithuanian Stanisław Witkiewicz and Polish Malinowski disagree regarding the merits of the Imperial Degree, develop insights into multiple geographies, which cross to sculpt the shared identities of the players. I sincerely believe that I unflatten Polish history by exposing this heterogeneous background, to provide a vision that is in no way less enthusiastic, but that instead unveils depth, drama, acts of valour, and contribution to arts and science.

I work all along to expand the boundaries of the Polish roots of the anthropological tradition, about which Dr. Grażyna Kubica published her book with Erest Gellner in 1988, to suggest that Polish anthropology should be dated back to Mickievičius who first used ethnographic “Volkskunde/Folklore” questionnaires to study ethnics. I unveil that we owe much to Mickiviečius’ unique way of conveying field data through poetic edification: writing “faithfully what you see.” Verbatim, he wrote: widzę i opisuję “I see and I describe” (composed as part of Pan Tadeusz), i wszystko wiernie odbijam “and I loyally impress everything” (present in Liryki lozańskie, Lyrics from Losanne), and sceny historyczne i charaktery osób działających skreślił sumiennie, nic nie dodając i nigdzie nie przesadzając “and he sketched historical scenes and the personalities of characters watchfully, adding nothing and exaggerating nowhere” (in Dziady Part III, Forefathers’ Eve). These seemingly simple ideas about the art of ethnography, related to nineteenth century romanticism, are the basic tenet of anthropological writing. Mickivičius was, no less coincidentally, on Malinowski’s university syllabus. Since Mickievičius was Lithuanian as was Witkiewicz, I bring back the Lithuanian theme into Polish history to vitalize my narration with intrigue and anticipation in memory of the Great Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland.

Translations of Mickievičius (and also some Młoda Polska poetry: Bolesław Leśmian, Jan Kasprowicz, Leopold Staff) weave a literary creation around my research, which uses literary interpretation of Malinowski’s diaries (and monographs) to propose in the end how Malinowski intentionally plans to expose his personal writing — probably to shock bourgeois society and — to set a new trend in anthropology.

This new trend is currently (since the 1960s) related to the so-called “reflexive turn,” which explains anthropologists’ recourse to autobiography in research (closely linked to diaries), enabling them to make subjective readings of field data.

It is this new trend, that I call “Writing in Schein” or “Scheinschrift” where the word Schein is German word for the production of shiny images, or ideas within a discourse, inspired by Apollonian art. —In other words, I purport that Malinowski’s anthro diary writing is the new artful research method (made in the image of Greeks) in its own right!

Although I start with an appreciation of the peacock-eyed ponds of Zakopane in relation to Malinowski’s life, romantically set to the rhythms of the golden dust that is Młoda Polska verse, my thesis is more of a theoretical piece about modes of anthropological writing. I would like. therefore, to break-down how I dialogue with major thinkers of anthropology, literature and philosophy regarding the production of knowledge. I am thinking in particular of Gilles Deleuze, Johannes Fabian, Edward Said, Etienne Balibar, Wolfgang Iser as well as all those who can be placed in the category of theorists of semiotics (those who encode source material onto signifiers) and theorists of discursivity (those who perfect emic knowledge via writing strategies) in the disciplines of anthropology, sociology, the humanities.

Gilles Deleuze is at the heart of my proposed theory of Writing in Schein because I am essentially importing his concept of Inverted Platonism into anthropology. The defounding of discourse (signifying in Greek a legein, inspired by the erotic question in search of truth) marks the passage between the hierarchy of the copy (and in terms of the study of knowledge, from the hierarchy of rationality) to the anarchy of various modes of writing including auto-fiction and free-style writing that embrace the lawlessness of selfhood and the “I”. The demerits of determinism are shown when it is proved that copymaking, that makes the hierarchy of the same and the like by making resemblance, is imbued with loopholes, mainly because it is systems-visualist, being premised on ladder systems of power and prior biases. I propose that knowledge is not made by copy (imitatio) but by virtue of an idea (inventio) where the anthropologist is the sophist or artist of a fantastic art, in which he reorders various forms of representation like a film maker reorders film cuts in a movie script. Writing in Schein is such play with forms and the mad literary simulation (Deleuzian concept) that makes shiny things, as I have stated above, in the image of Apollonian art (Sallis interpreting Greek art), ultimately justifying Clifford Geertz’s argument which presents the anthropologist-as-author. I end my chapter on Writing with Schein with the assertion that Malinowski is Sophist 267a-268b and wise man, because Malinowski surpasses his obligations in scientific imitation (imitation with knowledge) and dissembling imitation (imitation without knowledge). He meets the criteria of the sophist as outlined in Plato’s text and goes further in crafting the dialectical structure of the anthropological story, by aligning vignettes of knowledge and forms of representation (that take the ordered line R1, R2, R3 where R1 = monograph, R2 = diary,) for posterity, including that zeszyt, the diary, which I argue, is a premeditated organization of knowledge that is a part of a bigger pedagogical plan, whose objective is not the creation of copies that serve world memory like historical documents, but the creation of a tractatus that will unfold new questions: a revelation in the form of compte rendu or fable like a creation of belles lettres that will represent le sens commun and explication to stimulate a never-ending conversation.

My thesis is a response to Johannes Fabian’s thesis on temporal relegation in Time and the Other. I use his theory to show how Malinowski’s I-seeing, I-grasping, I-representing, I-telling cuts into power structures symbolized by the ladder system and La Fontaine’s poem about the wolf and the lamb. The I has a special power of overturning clock-based narration by virtue of making its deeds and made-objects sacred, thereby overcoming the linearity of 3D+T time since the I exists as if time-space had no dimension, and as if it were therefore 4D. Part of that undisclosed power is related to the question of human vulnerability, which is a chapter inspired by the work of Ruth Behar, (author of the Vulnerable Observer), which I actually took out of my thesis, but which exists as a published article in the 2012 issue of the Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford. What I do state in this thesis is that 19th century anthropology was written like a history, promoting ideas of fitness-impacting variations in human activity such as progress, that is most simply put, a way to pass off judgment onto the Other based on relative scales for comparison, to the point where Ernest Gellner accuses the greatest anthropologist of all times, James Frazer, of producing “theories of retardation” since he romantically sketches natives as members of a colourful bestiary, thereby as inferiors. I also break down the ways in which anthropology-as-history, that is a social science that considers the native as existing prior to itself, is the product of rationality, classification systems and various forms of mathematics in social science, which objectify and conflate the spirit of native and his Geist.

I answer Étienne Balibar regarding race-concept. He states that race-concept was considered fact-based when it should have the status of belief. This is insightful because it reiterates the importance of the mental, and of mentality studies, which Malinowski is known for having spearheaded. I draw a parallel between Balibar’s race concept and Thomas Picketty’s concept of capital in economics as something that is to be rethought — not as fact, but as belief, and illness of our time.

This ties in with Edward Said’s Orientalism or contrapuntality, which is the mobile axis around which anthropology and literature spin. Orientalism is amplified with my theory of phantasm, because the gap between n-as and a-as becomes wider and wider, showing that what permanently changes is the point of view, again of relevance to mentality studies.

I am a selective reader and the reason why I could not get my PhD off the ground for a long time was because I did not fully appreciate that I could do something with my fascination for the ideational departure of social fact into narration. My professional deformation consists in not being uniquely a literature student, whereby literature alone is too fictional to satisfy my cravings. My professional deformation consists in not being able in any way to meet the criteria of a social scientist because I simply do not write like one, and never could; not in the strict sense of social science such as sociology or history. It took Wolfgang Iser to help me get out of this impasse.

I do not know much about his other work but I know that he writes about figuration, and I fell under the spell of one of his concepts, the “as if.” It is a concept that catapults the subject into being through avowal and planned staging. Both Iser and Deleuze taught me about the semiotics of copy-making: about writing as the re-encoding of source-material by matching and the collation of signifieds and signifiers through retro- and pro-jections. The push for figuration comes from the “as if” or the phantasm, which installs image within the copy, letting us film back, set up anticipation, catalyze the energy of subjectivity, enable omission or ellipsis by allowing fast-forwards, and for expressing conditional futures. Wolfgang Iser and Deleuze taught me that discursivity is the energy of phantasm converted into sign, that enables Writing in Schein because it sets up the endless game of fiction as reality and reality as fiction, both in enacted worlds.

In my article on the “as if” for the International Journal of Anthropology at the Humankind Studies Institute at the University of Florence, I wrote that “There is absolved faith that authorship exhumes (digs out) the human differential.” It is precisely that: authorship digs out the essence of what’s human because it constructs it thanks to the “as if.” The “as if” is the means of figuration — representation driven by copy-making that tells us what things are like so that we can realize a — phantasm (target) driven by other phantasms of what we want to be.

So what is my contribution to knowledge? My contribution to knowledge comes from having rethought the reflexive turn in anthropology in terms of Deleuzian defounding. My contribution comes from having insisted that anthropology is much more than just the monograph; that it is also the diary (through planned diary unveiling following the mode of avowal). My contribution comes from having highlighted the conversions between forms of representation: — diary to monograph, monograph to diary, which indicate areas of slippage in the transliteration of data and figuration, a field where much new work may is yet to be made. And that Writing in Schein is not just the production of forms of representation: R1 = diary, R2 = monograph, but their ordering that enables discourse to be developed.

Diary unveiling is the process whereby the subjectum reveals itself as sum. It is the site of self-reporting and self-disclosure highlighting the concealed strain between objectivity and subjectivity: — texo (Latin word), a production — texo (Latin word) defined according to Virgil as construire une haie, defined according to Ovid as entrelacer des fleurs, defined by Cicero as ourdir une trame: in Polish, zbudować płot, spleść kwiaty, usnóć splot….

In that spirit, I want to close by reading the passage of my thesis in which I provide the most unique blending of literarity and social analysis in the vein of my research:

We have to study man, “and we must study what concerns him most intimately, that is the hold that life has on him.”[1] If self-reporting is authentic production, and economy is the management of resources intended for production, then the “economic man” is the authentic writer who puts a great deal of polish on the arrangement and general appearance of his garden, guided, like the native, by a “very complex set of traditional forces, duties and obligations, beliefs in magic [the case of the native], social ambitions and vanities.”[2] Malinowski wants to be a steward — to preserve, in the space afforded by language, the native as the archetype of universal man. In the journal, he explains that he desires to translocate in time the hymn to life, I interpret, into a crystalline matrix, by working through the sources of the self,“to smelt the creeping flame of the moment stoking the fire of one’s precious crystal, preserved forever in the vault of abysmal soul,” przetopić błysk chwili, płomień pełgający i trawiący na ogień własny drogocennego kryształu, przechowany na zawsze w otchłannym skarbcu duszy.[3] I provide the quote in full, below.

The garden — “Somewhere beyond right and wrong, there is a garden. I will meet you there,”[4] is an incarnation of shamanic spirituality-cum-exaltation vitalized by the “love of work, intoxication with the construction of [one’s] own work, faith in the value of science or art — [where] eyes on the work cannot see the artist — [where ambition arises] from constant self-view — romance of one’s own life, eyes turned on one’s own figure,”[5] the psychic conduit of grounding in blessings, fertility and abundance. Crystalline thoughts preserve, in the journal that is this garden, the precious soul of the anthropologist, immortalizing the hallucinogenic vertigo of stomping nothingness with a Titanic stroke of the blade of sorrow. The loss of innocence is made in sacrifice to consciousness, a doleful offering breaking the matrix of life “like steel cuts through iron, body and bone,”[6] which only the expansion of the instant of time can buy back. The exchange of youth for maturity, ignorance for enlightenment and obscurity for awakening becomes marked by the oxymoron of “sunny blindness of what combusts into joy,”[7] conveying the intensity of the loss suffered, needed to gain the satisfaction of self-understanding. This moment, defined by hot shivers at the inscrutable powers of the riddle of life, must be outlived beyond the tragedy of existential struggle and beyond the burgeoning consciousness that discovers it. The passage represents the acme of Malinowski’s literary expression.

Dr. Kubica will tell us more.

[1] Malinowski, Argonauts, 25.

[2] Argonauts

[3] Diary, 27.VIII.1912, 190.

[4] Rumi.

[5] Run-on-sentence. Diary, 5.VI.1918, 649.

[6] Diary, 27.VIII.1912, 190.

[7] Diary, 27.VIII.1912, 190.